Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

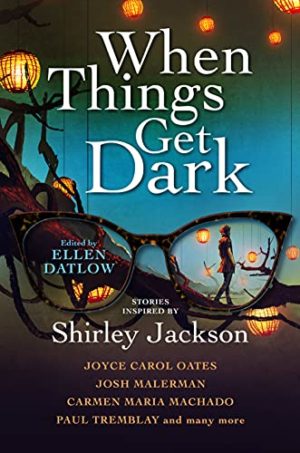

This week, we cover Cassandra Khaw’s “Quiet Dead Things,” first published in Ellen Datlow’s 2021 When Things Get Dark anthology. Spoilers ahead, but we encourage you to go ahead and read this one first yourself!

“To be human, Mr. Carpenter believed, was to work relentlessly from dawn to deep dusk, perpetually vigilant against the shadow-self.”

It’s bad enough that sneering urbanites view rural folk as inbred, livestock-humping, unhygienic bumpkins with a taste for bad politics and worse music. Now Asbestos and Cedarville must contend with the scandal of murder most foul—in an adjacent village a woman has been found “tidily flayed and bolted to a tree.”

Mayor Carpenter of Cedarville knows his duty is to sustain his constituents’ morale in the face of how civilization’s flimsy veneer. Toward this end, the town council maintains a bird-box outside the arboretum, in which right-thinking citizens can anonymously post complaints about their less upstanding neighbors. The Cedarvillians are overwhelmingly European in origin, of a “heavily dilute salmon in color.” Mr. Wong and his sister brought an “invigorating” whiff of the “exotic” to the town. The sister drowned; exotically, Wong maintains a shrine to her memory. Rich, thrice divorced Mrs. Gagnon has bird-box posted her suspicion that the Wongs were incestuous fornicators.

The murder is a matter of more urgency, however. Mr. Jacobson of Asbestos confers with Mayor Carpenter. Asbestos figures the killer’s an outsider. It proposes to close itself off for a few months and hopes Cedarville will follow suit. If enough communities band together, establishing barter systems among themselves, they can function in isolation for a while. After considering recent augurs—morning-news calamities and the flight of Cedarville’s “eerily astute” crows—Carpenter agrees to the scheme.

A few calls and a letter to the county authorities serve to officially liberate the rebel communities. A “frenetic joy” sweeps Cedarville, leaving the town garlanded and strung with fairy lights months before Christmas. Younger people joke about “agrestic paganism” and “memory…held in the marrow.” But all are busy with dances, visitors, feasts and “drinks to…guzzle and splash onto one another, whether in ecstasy or rage or some amalgamation of the two.” The changes nourish everyone but Wong.

Carpenter holds an assembly at which everyone appears in festive garb and mood, except Wong, who kills celebration by denouncing the border-closing as wrong. We’re sending a message to outsiders, Carpenter replies. Wong counters that “if there is a wolf here trying to eat us sheep,” it’s going to rejoice “that the sheep won’t make contact with their shepherds.” The killer is local, he contends, and no, the people of the county don’t “know one another to be good.” Wong knows they’re adulterers, child abusers, tourist cheaters!

Thus “laid bare without consent,” the townspeople feel not guilt but rage. Carpenter challenges Wong’s allegations: Does Wong think himself better than his neighbors? Wong realizes his danger. Nevertheless, he tells the crowd he’s more honest than they are.

And then something “happened with” Mr. Wong.

Winter comes hard to Cedarville. Snow and ice trap people in their homes. Mrs. Gagnon freezes to death in her woodshed—unless she was murdered elsewhere, then cached there wearing a “small thoughtful frown.” Another woman is flayed and affixed to a tree; her incongruous expression is melancholy, as if the corpse pities the living. Though food supplies dwindle, boys drive away Asbestos’s Jacobson and his offer of meat for trade; Carpenter urges self-sufficiency through hunting and fishing.

When the phone lines fall, he suggests people turn the “inconvenience” into an opportunity to turn from “the capitalistic existence espoused by the urban elite” and revert “to a more naturalistic state.”

Sunday mass becomes a daily event. That is, until the Elliots’ oldest daughter finds Pastor Lambert pinioned to the life-size crucifix, thoroughly disemboweled. Miss Elliot says she saw a woman’s silhouette in the window of Lambert’s office, and smelled an incense like the one that used to cling to Mr. Wong. Later Miss Elliot is discovered hanging from a ceiling beam in the empty Wong house.

The townspeople assemble in the church. The mayor reminds his constituents that he is always available to them, but Mrs. Elliot proclaims that what happened to Mr. Wong wasn’t right. “The woods know it,” she says. “It’s punishin’ us for that.”

Carpenter’s sympathetic platitudes fail to placate her. “We’re going to die for what happened,” she prophesizes, adding that “it” said Carpenter was next.

Next morning finds Carpenter dead in his armchair, brains plastered on the wall behind him. Breakfast, the gun and unopened mail sit neatly atop his desk; on his face is that small, thoughtful frown common to all the deceased. Next day the constable dies. Then the Elliots in a house fire. And so on as Mrs. Elliot predicted: deaths “as inexorable as time.”

What’s Cyclopean: Khaw revels in succinctly disturbing descriptors, from Mrs. Gagnon taking sacrament “like a harlot traversing her wedding night” to the blizzard where “to breathe was to abrade lungs, leave mouths bloodied from the kiss of the chill.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Rumor accuses the residents of Asbestos of marrying cousins, having “nonconsensual coital relations with the livestock,” and generally having bad hygiene, politics, and music. Neighboring Cedarville finds these topics insufficient fodder for discussion, so also fascinates themselves with their sole Asian immigrants, the Wongs, despite their awareness that one isn’t supposed to consider one’s fellow humans “exotic.”

Weirdbuilding: The story resonates with not only Jackson, but the whole history of stories sharing Mr. Carpenter’s conviction that civilization is “a veneer under which still rutted and writhed all kinds of paleolithic barbarisms.”

Libronomicon: No books, other than possibly some misused bibles.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Mr. Carpenter accuses Mrs. Elliot of “catastrophizing” following her daughter’s death.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

At the start of The Haunting of Hill House, I said, “I would honestly be happy with an entire book of closely observed, dryly snark-ful biographical sketches.” Hill House is, of course, not any such book, but sleds wildly down the slippery slope from snark to fatal denouement while remaining engaging all the way. It’s a hell of a trick, and an impressive one to mimic in the space of a short story. This Khaw manages with their usual blood-soaked panache. The little digs at the judgy small-town characters are fun… until they aren’t. Until they become less little, less gentle… less forgivable. And less forgiven, too.

Those early bits, though! I am still not over the history of the local arboretum outside which sits Cedarville’s suggestion box. Farmland, then a community garden, a greenhouse, “a short-lived manor torched to its bones by the young daughter of the last family to inhabit its walls,” several pubs, a pet cemetery, and Mr. Wong’s corner store. Aside from the multiple pubs, none of these involve either the same sorts of buildings or the same sorts of landscaping! It’s ridiculous and delightful and feeds directly into the darker absurdity at the story’s root. There’s some kinship between Cedarville and the unnamed lake town of “The Summer People.” Small towns follow their own logic, and you might not want to follow too closely behind.

In addition to the Jackson homage, I’m pretty sure this is our first piece that’s clearly influenced by the coronavirus pandemic. On which front it’s similarly on razor-sharp point. People are dying; let’s close the borders! Let’s close the borders against the people who are helping us out! Find some scapegoats! (Harking back, of course, to “The Lottery.”) People keep dying; should we maybe try to handle things differently? Of course not! If more people die, you have our condolences.

Interestingly—and unlike the actual pandemic—the questions set by the opening paragraph are never answered. In general, when you open with a mangled body, you’re going to either solve a mystery or meet a monster. The manglings will get more bloody, the danger will get more visible, and some sort of explanation will be revealed. Only it won’t. Because in this case, it doesn’t matter whether the bodies are produced by a mundane murderer, a supernatural monster, or the harsh justice of the woods. The only body for which we know the cause—if nothing else—is Mr. Wong’s. That death and all its details stay offscreen, and everything else revolves around it. Perhaps it’s because so many horror stories, not to mention mysteries and war films and news articles, have opinions about whose deaths matter. So here, the death that would normally remain invisible does remain invisible, but also does matter deeply.

The option for the killer that I left out, above, treads the fine line between mundane and supernatural: the ritual sacrifice. The whole story dances around this idea, leaving a sort of sacrifice-shaped negative space. Several (though not all) of the described deaths appear ritualistic, and the “thoughtful” gazes of the dead suggest a very unusual sort of experience. Mr. Carpenter is aware of himself as “an effigial figure, something to burn should the winter linger past its welcome.” The celebrations in self-isolated Cedarville are bacchanalian, primordial. Revelers joke about “how bucolic practices were often scaffolded on grisly traditions.” And preparations are cult-like: “This was about community. There was no opting out.”

And, indeed, there’s no opting out, for anyone in Cedarville.

Anne’s Commentary

In the introduction to her anthology of Shirley Jackson-inspired stories, Ellen Datlow writes that she wanted contributors to “reflect Jackson’s sensibilities” rather than to “riff on” her stories or fictionalize aspects of her life. Two verities that tickled Jackson’s sensibilities were how “the strange and dark” often lurk “underneath placid exteriors” and how “there’s a comfort in ritual and rules, even while those rules may constrict the self so much that those who follow them can slip into madness.”

Cassandra Khaw plays with these verities in “Quiet Dead Things.” No wonder Mayor Carpenter believes humans must remain “perpetually vigilant against the shadow-self”—iceberg-like, the people of Cedarville flaunt sunny personae above the waterline, while hiding subsurface their massier dark sides. A realist, Carpenter knows his job is not to dispel shadows but to maintain community morale via the “ritual and rules” that keep the shadows hidden, both to outsiders and his citizens themselves. Somebody’s got to do it, and only Carpenter’s willing to risk becoming “an effigial figure,” should municipal affairs go south.

In Cedarville, unfortunately for him, it’s not effigies that get sacrificed. Cedarville demands flesh-and-blood victims.

What else would smirking urban elites expect from benighted rural folk? Asbestos and Cedarville have already endured too many accusations of incest and bestiality. Maybe even incestuous bestiality, given how the former outrage begets subhuman monsters! Is it really a big deal to add ritual murder to the list of their depravities?

It’s a big deal to Asbestos and Cedarville. Their authorities insist an outsider must be responsible for such unsavory homicides. A transient like a truck driver or an occasional ceramics buyer or that rich couple with the vacation cabin or teenagers on retreat. Or, as Carpenter cautiously implies to Jacobson, some “exotic” like Mr. Wong.

Wong is the only Cedarville resident who doesn’t believe in the outsider theory. He has no difficulty believing their wolf-in-the-fold is a local, because he observes the locals from the perspective of someone perched between Outside and Inside. For exposing their sins and hypocrisies when the Cedarvillians are at the height of their isolated self-congratulations, Mr. Wong must have… something… happen to him.

Khaw leaves the exact nature of that something a mystery, only noting that Wong ends up “gone,” his house “gored of its contents” and “strung with police tape.” That such mysteries abound in Cedarville and environs, barely but provocatively hinted at, is the story’s chief joy for me. Where the arboretum now stands, there was once a manor “torched to its bones” by a daughter of the resident family. Mr. Jacobson from Asbestos has gore-encrusted fingernails; maybe Jacobson is a legitimate butcher from a town of butchers, or maybe that blood has a less “justifiable cause.” There are “things” that live on Richardson’s farm; all we know about them is that they are keen scrutinizers. The local crows are “uncommonly large and eerily astute.” There are “black dogs in the woods, hounds with a corona of headlight eyes.” The woods is the supernatural judge and avenger Mrs. Elliot names only as “it.” Miss Elliot sees a flickering female silhouette in Pastor Lambert’s window, smells incense like what Wong burned before the shrine to his sister, pulled many years earlier from the lake—accidentally drowned, or murdered, or a suicide? The same can be asked of Mrs. Gagnon, and Miss Elliot, and Mayor Carpenter: Were they murdered, or did they kill themselves?

Through a pervasive constellation of weird details, Cedarville’s Christianity shows an unsettling face. The crucified Christ in the church is gruesome in his emaciation and pained ecstasy; instead of sporting the traditional spear-slit discreetly bleeding a drop or two, he spills guts from a gash. Later Pastor Lambert dies nailed over this Christ, even more spectacularly eviscerated. In isolation, Cedarville decks itself in wreaths and red garlands and fairy lights that feel like but are not Christmas. The celebration is “something older,” perhaps “agrestic paganism,” but then again, didn’t everything Christian begin in blood? Townspeople are titillated by the Wongs’ “refugee gods” because they imply a superstitious life “unburdened by Christ.” Unburdened? That’s a curious and telling choice of words. The women ritualistically murdered are affixed to trees, and Carpenter believes that people who expect too much for too little will end up “nailed to a tree, throat and temples and trunk woven with a stigmata of thorns.” Christ’s crucifix is often called a “tree,” and he bore a crown of thorns onto it.

At the least, the specific species of the “Christian phylum” that Cedarville comes to practice is unorthodox. The town was going its own way, trailing dark secrets, before the murders began. The murders gave it an excuse to go still farther, claiming “amnesty” from the outside world and sinking joyously into isolation. Initially Cedarville allies with Asbestos and other communities, but its isolation continues to tighten until even Asbestos (in the form of a meat-bearing Jacobson) is driven off. Nature conspires in the town’s efforts, encapsulating it in snow and ice and bringing down phone lines, its last connection to modern technology. Mayor Carpenter spins the “new silence” into a “homecoming,” a “reversion to a more naturalistic state.” The Cedarvillians ought to be comfortable with their slide back in time. After all, they’ve always harbored anachronisms like Mrs. Gagnon’s over-decorated hats (“fascinators”) and the young people’s decidedly 19th-century finery, bonnets and waistcoats and mother-of-pearl buttons. And what about the antique rifles the young men tote? I wasn’t sure of when this story was taking place until Khaw nonchalantly slipped in Carpenter’s use of email; circa 1930 or 1950 I was thinking, so the sudden jolt into the 21st century was a neat trick of re-disorientation.

In any case, Cedarville is cursed. Whatever its historical iniquities and modern sins, it may be that the town’s damning act is a steadfast denial of reality in favor of believing what it wants to believe. As Mr. Wong understands, “Truth was merely raw material. It was the story, the consensus belief, that mattered.”

Next week, we continue P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout with Chapters 7-8, in which Maryse looks for monsters to help hunt monsters. This monster-hunting strategy, we suspect, is really not going to pay for itself.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out in July 2022. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic, multi-species household outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

This has become one of my new favorite scary stories! I have always loved tales of small towns hiding something rotten inside. This may be because I grew up in an entirely pleasant small New England town that is completely unlike any scary stories set in one. But, my family were still ” blow ins from New York ” when we got there (though both I and then my father have served as trustees on the local historical society, so I guess we’ve gotten over that moniker).

In this story, Klaw builds such incredible atmosphere, and so deftly defines the character of these small-town small-minds. I was horrified for Mr Wong the moment we met him, but it wasn’t until Ruthanna pointed it out that I even noticed the pandemic-age analogies being explored! Chalk it up to shallow reading or perhaps complete immersion in this little world. I think it is a very apt companion piece to Ring Shout, where the monsters very much exist because / are human bigotry.

@Moderator Can you please link this post up with the main Reading the Weird page?

@2 – Done, thanks!